Interview with Graciela Sacco – Review

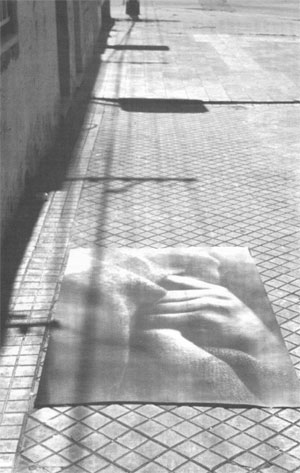

Cuerpo a Cuerpo XXIX (Body to Body XXIX), 1996/2000

In the interior of the houses wooden ceiling is generally substituted for plaster; and it is usual for all the apartments of the same floor to communicate above the partitions, which do not extend entirely to the top or cornice of the room. This allows a free circulation of air, which is so essential to comfort and health in tropical climates. The lower floor is occupied as a coachhouse and stables, and visiters cannot reach the family without passing the family coach, which is kept in fine order. This custom takes its origin from the fondness for show which is innate with the Portuguese and Spaniards. The entrance-door is properly a large gate, which is constantly watched by a Black slave in livery, who manages to keep awake by sliding his thumbs over a “marimba.” In the lower windows, close trellis shutters, hung from above horizontally, answer all the purpose of glass.

The streets are narrow, always dirty, and intersect each other nearly at right angles. In their centres run small streams of water, which are usually the vehicles of filth; and when it rains, which it does, and very heavily, during a considerable part of the year, the whole street is overflowed. The side walks are very narrow, and the dress of foot passengers is always in danger of being soiled by the splashing of horses and carriages.

The cries of the town are indescribable: the ears are assailed with the shrill and discordant voices of women slaves vending fruits and sweetmeats; and of the water-carriers crying “agua,” which they carry about on their heads in large wooden kegs, filled at different fountains: each one is worth about six cents.

The marketplace is a filthy collection of booths, generally surrounded with mud, under which is sold a variety of vegetables and fruits. The yam supplies the place of the potato. The oranges are amongst the finest in the world, and are sold at from ten to twenty-five cents the hundred. Butcher’s meats are sold in shops which may be scented from afar, proclaiming the state in which they are kept. It is customary to require the purchaser, after selecting what he wishes, to take also a piece of an animal that may have been killed three or four days; and, if he refuse, the butcher most obstinately witholds the chosen morsel. The beef is tender, but entirely destitute of fat, and would be much better if more care and cleanliness were bestowed in the butchery. The pork is very good; but the mutton is bad, and extravagantly dear. The poultry is indifferent, and far from being cheap. The fish-market is a very good one, generally well supplied; oysters are found in the bay, but they are not much esteemed. I am told there is a market for monkeys and parrots, but I did not visit it.

I am happy to state that I sought in vain for the slave-market which I visited in 1826. By the common consent of the Christian world, the traffic in slaves has ceased; yet I am told that some have been imported, clandestinely, since 1830. At the time I visited this market, I saw the poor slaves, seated on benches, thirty or forty together, and entirely naked, except the loins, which were covered by a fold of blue cotton cloth. Many of them were suffering from the small-pox or just convalescing. While I was looking into one of these stalls of human life, a lady, attended by two servants, entered, and gazing round at the group, fixed her eye upon one, and after surveying him well, as a practised jockey does a horse, she inquired the price. The merchant ordered the individual indicated to get up, and then put him through several exercises, to show that his motions were perfect. All this took place with the same indifference, or more, than is evinced generally in a bargain for a pair of gloves.

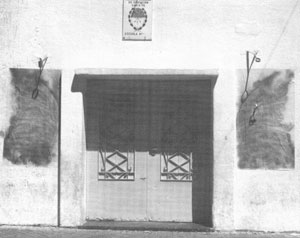

Sin dirección fija (No Known Address), 1998

Marguerite Feitlowitz: Your work fascinates me. We enter, we see, we’re immediately inside. What impresses me is that the art is political, engagé, but in no way narrative.

Graciela Sacco: I think for me the definition of “engagé” is the genuine intention to inscribe oneself in a different place. The space is always integral to the work, and sometimes in ways that go beyond one’s original plans: The Everlasting Combat [which shows a popular demonstration, with the man in front throwing a stone toward the viewer] had articular resonance when it was exhibited in the museum in Rosario, Argentina. At the VI Havana Biennial, I was assigned to La Fortaleza—unbeknownst to me to the very cell that had been occupied by Reinaldo Arenas. So there the work had a whole different charge, a whole different frame of reference. I don’t ‘occupy’ the space in the sense that I’m making a statement. Rather, every space is for asking questions. Every image should start a dialogue.

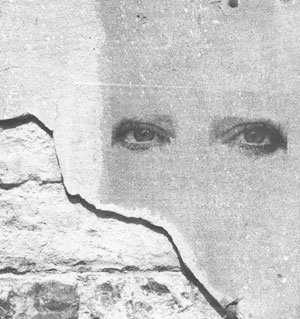

MF: Your work tends to portray, or imply, a lot of other people. We confront a multitude of eyes, a multitude of mouths, masses of individuals pressed together in political uprisings. It’s work that is highly populated, of the street. For me, the installation space is at once communal and atomizing. A very interesting tension. One is continually disconcerted. Eyes watch us from the walls; a man points a gun directly us, making us extremely self-conscious about the flashlight we are aiming at him. There seems to be no boundary, we’re unsure as to where, exactly, the exhibit begins, who and what is on display. Especially with the eyes, there’s a kind of crisis. Should we look? How can we look away? Okay, they’re not human beings, but they’re eyes. The most human feature of all.

MF: Your work tends to portray, or imply, a lot of other people. We confront a multitude of eyes, a multitude of mouths, masses of individuals pressed together in political uprisings. It’s work that is highly populated, of the street. For me, the installation space is at once communal and atomizing. A very interesting tension. One is continually disconcerted. Eyes watch us from the walls; a man points a gun directly us, making us extremely self-conscious about the flashlight we are aiming at him. There seems to be no boundary, we’re unsure as to where, exactly, the exhibit begins, who and what is on display. Especially with the eyes, there’s a kind of crisis. Should we look? How can we look away? Okay, they’re not human beings, but they’re eyes. The most human feature of all.

GS: Absolutely. And what you feel with the images, also happens with the shadows. Which is your shadow? Which shadows belong to the work? You know the old saying. They’re all the same in the dark.’ But it’s more conceptual, it’s taking the social arena into a dark space. Which is what it is, after all. I mean, a person throwing rock at you in the street, even in broad daylight, that is not a transparent act. It’s a dark act, which you never end up seeing completely.

MF: The materials you use are very strong. Objects like the suitcase, the table, a curtain, a window blind, the things of everyday life.

GS: They’re things we often don’t see, they’re simply there. Except for the suitcase, Inch is always provocative. The blinds are the ones you find in any public office, the offices that determine which immigrants will stay in the country and which will not. For the most part, the images I print on the blinds are of immigrants. One series shows a group of Bosnians, [from the series "Outside"] arriving I don’t know from exactly where, but the faces of these women are so traumatized and determined, like they’ve already been through everything, yet the action has yet to happen, the plot has yet to unfold.

MF: Yet for the viewer the experience is more immediate than imminent—

MF: Yet for the viewer the experience is more immediate than imminent—

GS: Of course. Because we have a live connection to the image. Even if we don’t know that these women are Bosnian, we see their faces on these homely, totally familiar blinds. Seeing them together puts them in a new, intermediate place.

MF: You’ve said that you think of objects in a “primitive” way, as things that have a great deal of life within.

GS: Right. Here’s an example. I was walking along and saw a soccer ball abandoned in the street—all collapsed and dirty. So I took it home and printed a big mouth on it with the words Ay, de mi! [Woe is me!]. How can I put it? Especially in Latin America, this soccer ball—which was conceived to be kicked until it’s no good anymore—has a whole social resonance. There is a whole history of art right there.

Entre Nosotros (Between Us), 2001

MF: What are you working on now?

GS: Something that began with the mouths. People would come up to me and ask if this or that one was the mouth of an animal. “No,” I’d say, “it’s human.” But it got me to thinking. What is the human state? What is animal? It isn’t so easy to say. Have you never noticed how people sometimes comport themselves like animals? Especially in groups? And if you think of how they express themselves? That’s what I’m exploring these days. Boundaries and limits, but related to animals and humans.

MF: Do you know that Darwin’s last work was On the Emotions in Animals?

GS: You’re kidding. I’ll have to read it. Now there’s something I should tell you. Those eyes you were mentioning before? Not all of them were human.

En peligro de extinción (In danger of extinction), 1994